Knowing How to Learn Is More Important Than What You Learn

In Conversation with Michael Horn: Co-founder, Clayton Christensen Institute.

For those readers in the US, please enjoy the Thanksgiving holiday. Feel free to use some of your free time to read all the way through and to share with friends :) Stay healthy, stay safe!

Knowing how to learn is more important than what you learn.

I was thrilled to speak with Michael Horn, a man whose life’s work has been to transform learning worldwide. His mission is to create opportunities for everyone to build their passions and fulfill their potential through education. As Co-founder and Distinguished Fellow of the Clayton Christensen Institute, Horn developed expertise on disruptive innovation and blended learning. He became well-versed in the field of online learning as the Director of the Robinhood Education + Technology Fund and as the Chief Strategy Officer at Entangled Ventures, and has grown the viability of competency-based learning as a Senior Strategist at Guild Education. In a career dedicated to student-centered education, Horn has a one-of-a-kind perspective on the challenges we face trying to develop the new rules for (the future of) education.

Some of my favorite takeaways from Horn:

Why teaching is different than learning;

The need for a New Social Contract;

Building pathways and systems as a precursor to learning; and

Myth busting my own perception of what it is to be a student.

Let’s jump right into why sometimes it is better to be lucky than good.

As I often do during these conversations, I try to find out why someone has chosen to work in the future of education/work domain and what keeps them coming back. I'm always curious about what specific problem they are trying to solve. It not only helps me understand the makeup of the people in this industry, it gives me a better sense of the shared values that govern the domain. Most folks I’ve interviewed have a personal story that propelled them into this work. They might share an anecdote of a family member who was an educator, a story of how technology has reshaped the way they were able to learn, or a problem they had themselves that they wanted to solve for others. Horn’s story is different. Although some might call it "fate," Horn believes he found his career by accident.

MH: I was at Harvard Business School trying to get away from public policy. It was in a class taught by Clay Christensen, which literally changed the way I saw the world. The theories of innovation that he taught didn't just impact how I saw business but every realm. At the end of class one day he announced, “if anyone's interested in writing a book on Public Education with me, to stop by.” I stopped by. Not about the book but about a paper I had written for his class. At the very end of that meeting I said, “did you mean co-author a book with you?!” And he said, "yeah, I need help."

What was supposed to take a year took two. What was supposed to be just helping to write a book became helping to Co-found the Clayton Christensen Institute. And what Horn thought he wanted when he entered business school completely changed. Horn became so passionate about the ideas that he and Christensen were writing about, it altered the course of his life’s work.

MH: Unlocking individual talent and allowing people to build their passions means that there's never a day I'm not excited about the work I am doing. I love the fact that I can dance across the landscape and think daily about what it means to develop individuals in a very holistic way.

It is not every day that you’re given the opportunity to co-author a book with Clay Christensen. Horn recognized this initial opportunity and catapulted it into a career designing the future of education. And it’s not every day that you get to ask the guy who co-authored a book with Clay Christensen about what the future of education means for the future of work, so here we go!

Meet the Learners Where They Are.

Getting an education, going to school, studying, and doing homework are all associated with being young. I am here to break that misconception, even if just for me. When I hear the word "student," I am conditioned to think of young children sitting quietly in a classroom learning math or music. In my conversation with Horn, he points out that the largest percentage of current or potential students are the ~88 million adults in the US, and many more worldwide, that require upskilling and reskilling. They are known simply as the "working adult student."

Adults students are getting education in all sorts of places. They are studying and doing their homework. Adults are learners. We learn every time we read a newspaper, watch a documentary, or eat new foods. We are constantly learning both implicitly and explicitly, in every context. But learning continuously and being taught are two entirely different things. Preparing for our conversation, I fixate on a point that Horn repeatedly makes:

We don’t learn when someone is ready to teach it to us, but when we as individuals are ready to learn. You simply can’t make someone learn who isn’t ready for it.

I agree. But I also wonder, as we develop new adult-centered learning programs, offer new types of credentialing, and democratize the distribution of education, is it all doomed to fail with unmotivated students? Is motivation the most important learning trait?

MH: Ultimately all individuals are motivated. They all want to make progress in their lives. If we want education to be effective, it's got to help them make progress in the areas they're prioritizing. It can't be the school's or employers' sense of progress. It has to be the individual's sense of progress. It doesn't mean you can't help shape people's priorities by shaping the context or asking interesting questions that they never thought of. But I think we can only do that if we situate ourselves in that learner's journey of progress.

Meet the learners where they are. Don’t force them to come to you.

But how do we know what to study? Courses we'll enjoy most? Benefit us the most? Motivate us? How at age 18, at 20, or even at 25 are we supposed to know the career we want? If you’ve been following this newsletter, you already know I don’t entirely understand the value of pursuing a four-year degree at age 18 outside of the coming of age experience. Microlearning and A/B testing your education needs to be a more common path. Using a mix of the brevity of microlearning and real-world working experience, students could discover not only what they like and don’t like, but what type of work energizes them and what type of work depletes them.

MH: I don't think four-year college is the right solution to start for everyone. It might be at some point, but my own take is that education should start with you, meaning micro explorations into who you are. Couple this with quick learning experiences, which might be courses, internships, or even jobs. It might be starting a company. You should get a set of experiences that allow you to learn about what's out there and what resonates with you. As you start to get a clearer picture, then you're like, “oh, these are the things I don't know. These are the questions I have.”

It's often said education is wasted on the young. I think that's because [at a young age] we don't know what the right questions are or what the possibilities are. I think there would be a far better way for a lot of folks to learn. I think it'd be ideal if employers stopped requiring degrees so that they could facilitate hiring a more diverse set of candidates who can straddle higher education and the world of work. It would lower the cost of hiring if your [new employees] didn't incur four years of debt and opportunity costs.

Why isn’t this common practice in America? Some of you may be aware of Germany's apprenticeship programs, and how it is a large part of the education system and resulting manufacturing might. But this approach generally doesn’t exist in the US or even the rest of North America for that matter. Why? To some extent, who cares, the question is what can be done now? It is time to write a new social contract between employers, employees, and traditional education.

The New Social Contract.

The factory model of education, which is still very commonly used today, borrows from the late 18th Century Prussian education model. THE 18TH CENTURY!

There’s the belief that this model, which took an impersonal, efficient, and standardized approach to education, was adopted to help groom children into productive members of an industrialized economy by building an educational system modeled on factory methods. This meant assembling masses of students (raw material) to be processed by teachers (workers) in a centrally-located school (factory). Factory owners require docile, agreeable workers who show up on time and obey their managers. Sitting in a classroom all day listening to a teacher was good training for that.

[Fun Fact: Even though it is widely believed that the Prussian model was indeed designed with an industrial economy in mind, read here for an interesting argument to the contrary.]

Whatever side you take in this fight, you can’t debate the fact our current educational system has been around for well over 100 years, with only minimal change. So in a world where it is now common knowledge that we all learn at different paces, enter classrooms with diverse backgrounds and aptitudes, isn't it time for a new education-employment social contract? One providing a personalized learning approach to maximize both potential and ability? Horn, who acknowledges the need for reinvention, calls out the Northeastern's co-op model as an example of what should be more commonplace.

The objective of the [Northeastern co-op] program is to give a student the opportunity to explore different career paths, to begin building a professional network, and to acquire practical knowledge and skills. “Students learn more skills while working on a co-op program, which can then be integrated into the following semesters of the academic program.”

This model includes opportunities to study and work abroad, adding for increased diversity in both how and where students learn. This tact increases resilience, adaptability, and communication skills, all of which are increasingly valued in the world of work. Horn shares that part of resetting this social contract includes acknowledging 20-year olds are inclined to work this way already. We need to more explicitly structure their existing real world experiences as learning experiences.

So what does this model look like at scale? One where you don’t need to commit to a 4+ year degree program, but still experience how theory and practice work together? Without going into large sums of debt. Without being judged for jumping around.

Building a System to Learn

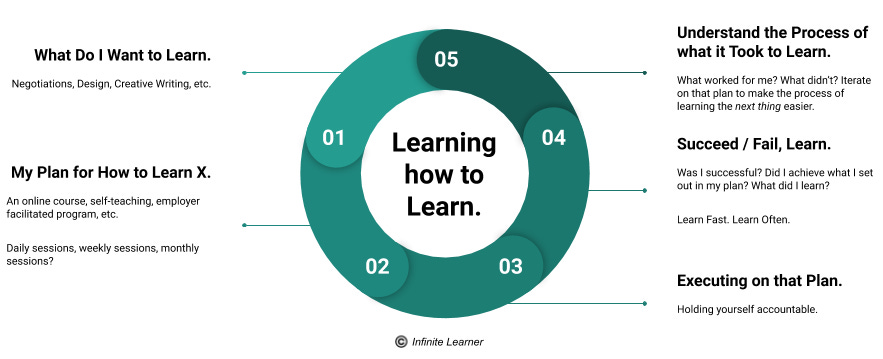

The government has always been in the business of education. Employers are increasingly getting into the business of education. But no matter who comes and goes, it’s ultimately always going to fall on the learner to assess what’s best for them. That’s why building a system for learning, building a plan for how to continuously learn, is paramount for success. Horn reminds me of an obvious, but often overlooked reality: the existing system isn’t designed to optimize for continuous learning. It’s built for young people. It’s built for one-and-done. That’s why metacognition, the act of learning how to learn, is the best path towards building intentional learning cycles for the working adult learner.

MH: I think we need to be teaching people how to be lifelong learners. That means helping them understand metacognition and build the skill sets to intentionally create a process where they start with a question, and make a plan for how they're going to learn and answer it. Then they go and execute that plan. Then you need some sort of assessment or reflection that causes them to tweak that, and then they go around the cycle again until they've gotten what they need.

The key learning for me is how important personalization is in the learning process. We have the opportunity now to change the design of adult education to meet this need. Adult learners should be given the time to not only understand what they want to learn but the best way for them to actually learn it. In this rat race of life, we often don’t get the chance to step back and build the system, the scaffolding, to make things easier for ourselves. In the journey of lifelong learning, understanding how you learn is the best investment you can make.

Emphasizing personalized learning also means changing our perception of the role failure plays as part of the learning process. Although credited to many, the ideology of "fail early, fail often" has more recently been attributed to Silicon Valley startup culture. Through our conversation, Horn and I agree this mantra not only falls short, it literally fails. It minimizes the fact that every time you fail, you have the opportunity to learn. I think it is time to promote a different version of this phrase: Learn Fast, Learn Often.

By viewing failure in the context of learning, rather than as its own isolated thing, the cost of failure goes away.

Knowledge and Skills and Measuring Success.

"Metacognition, executive function, and agency," Horn practically sings when I ask what skills are currently the most valuable in the workplace. However, for Horn, acquiring skills are only one part of the process of learning something new. For him, gaining knowledge in an area is the prerequisite to deciding what skills to acquire.

MH: What I really need to know, for example, is the logic behind computer programming. How to frame the problems and how to structure the code efficiency. I can only do that if I learn the knowledge, but it can't be about the knowledge for its own sake. By learning the content and knowledge, it helps you know what questions to ask. It can’t be about rote memorization and knowledge for knowledge's sake. Knowledge is important as a conduit to learning the skills.

[Interesting fact: Knowledge vs. Skills. Vs. Abilities

Knowledge: Knowledge is an organized set of mental structures and procedures. Learning takes place when there is a change in these mental structures and/or procedures.

Skills promote further learning and comprise content, processing, and problem-solving. Processing skills such as active learning, critical thinking, learning strategies, and monitoring contribute to more rapid acquisition of knowledge and skills.

Abilities are enduring and developed personal attributes that influence performance at work.]

Knowledge is something we should all be striving for, in every field, at all times. Focusing too much on one skill or set of skills, especially those categorized as hard and modular-based, is short-sighted, particularly given the pace of change for what skills are in demand at any given moment.

MH: I was at a wedding with some friends where they were saying they wanted their kids not to study arts and music and only study coding. I shared, “you know by the time your kid is grown. I’m pretty sure that computers are going to be coding themselves. The differentiation will be in the arts, design, and music.” Whatever is rules-based becomes brute force, even if it's not purely physical but mental. We can say with certainty that when something becomes rules-based, and we can start to automate it, it becomes a commodity and is less valuable. The flipside is also true, that which is more intuitive and sort of gut feel and is harder to understand, remains more valuable. That's where differentiation and value tends to get created.

But how do we know when we have perfected those areas that are less binary and more intuitive? How do we acquire valuable, necessary skills that elude definitions of quantifiable mastery? Can we create a system to codify something like communication skills? Horn thinks so. He extends this idea even further by calling for a deeper system of external validation, one with rubrics to efficiently measure the mastery of integrated skills. He mentions the idea of learning coaches, someone who can enable personalized micro learning, someone who identifies specific communication needs and tracks proficiency of communication in a given context. A coach that helps you split focus on hard skills and soft skills equally, and focuses on helping you get a job where every single day you are going to practice that skill you need most to succeed in the world of work.

The idea of using a learning coach brings together all of the principles Horn and I have been circling. And though having a coach might not be the singular answer to the question of improving lifelong learning, it's a start as more options become available to learn these skills. We will need to figure out a way to personalize, normalize, and document them so everyone can get credit for the learning they’ve done.

Ultimately it is time for every learner to challenge their assumptions about education. We can no longer limit ourselves to what worked in the past. Every individual, every working adult student, has the chance to create a personalized, student-centered education. It is time to focus on building the pathways to ensure that whatever skill is being taught, that you are ready to learn.

After School Activities with Michael Horn:

Read his most recent book Choosing College: How to Make Better Learning Decisions Throughout Your Life.

Read his latest for Forbes magazine.

Great article!

Really agree with "It's often said education is wasted on the young. I think that's because [at a young age] we don't know what the right questions are or what the possibilities are."

I don't think I actually learned how to even begin to ask good questions until I took learning into my own hands during college, mostly through the reading of a shit-ton of books. Even in college, there were probably less than a handful of classes that really taught you HOW to think, not just what to memorize (and subsequently forget).

I recently came across this article by Paul Graham: http://paulgraham.com/think.html, which I think is something to consider, especially if you're young. Sure, one might not agree 100% with everything in there, but at it's core, the point is to encourage first-principles thinking, and to think in questions, not statements.

Also agree with learning fast and iteratively. Treating the learning process as a continual experiment on taking action with learned knowledge is the fastest way to collect data and test your assumptions and process. Treat that experimental process like a mental laboratory, and make sure you are interested in the topics you're testing.