A self-prescribed learning addict, Scott is best known for being an "ultralearner."

His foray into ultralearning started in 2011 with the MIT challenge, when he used the institution's publicly available material to successfully complete its entire 4-year undergraduate computer science curriculum in 12 months! He also gained accolades for his Year Without English, a traveling autodidact program that led him to learn Spanish while in Spain, Portuguese while in Brazil, Mandarin Chinese while in China, and Korean in South Korea.

Scott's also written 1300+ articles and a handful of books on topics ranging from productivity, to career advice, habit mastery, and goal setting. He’s been championing "the best way to learn" for more than a decade! So you can imagine my excitement when I had the opportunity to connect with him recently.

We chatted in detail about his path to becoming an ultralearner including:

The shared secret to success for ultralearners across the globe;

Being okay with being bad;

The skills-fulfilling prophecy; and

Mastering the storytelling medium.

Enjoy the conversation and, as always, let me know if you have any feedback for Scott or me in the comments!

Full disclosure: I found Scott’s work as part of my own learning journey and have since read Ultralearning and completed his and Cal Newport’s course, Life of Focus.

Ultralearning is a strategy for aggressive, self-directed learning. Self-directed means that, rather than waiting to pay for expensive tuition and tutors, you can take back control. Aggressive means that, instead of spending years at something without getting great, your limited time and effort are always directed towards what works. - Scott H. Young

Not All Heroes Wear Capes.

Like most great endeavors, ultralearning was born out of a personal passion. While some people might aspire to be an Avenger or a star athlete, Scott’s superheroes were always those taking on ambitious learning challenges. Whether it was Benny Lewis, the Irish Polyglot and founder of Fluid in 3 Months; Steve Pavlina, who graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Computer Science and Mathematics in only three semesters; or Josh Kauman who developed the Personal MBA, Scott admired those who took on an ambitious personal learning challenges and succeeded. What caught his attention was not strictly their accomplishments but the way they documented their efforts for the world to see, sharing their learning system to all of those who were interested. This was all the motivation Scott needed to start his own ambitious learning project.

SY: I was interested in programming as a skill, and going back to school seemed really arduous and unnecessary. And so, my first project was the MIT challenge. I went into it from the perspective of, "Wouldn't it be great if I could obtain a degree without going back to school?"

Looking back now (after having been immersed in this world for over a decade), there is a strong career rationale for understanding how learning works and how self-education works to improve the ability to learn things.

But if I'm being really honest, the initial motivation for all this was that's really cool!

This got me to wonder whether being inherently interested in something "really cool" is enough to succeed in doing something incredibly difficult? Could the Ultralearning method truly be adopted by anyone?

SY: The kind of person who is going to pick up a book called Ultralearning, read it cover to cover and find it interesting, that’s already self-selecting. Some people have asked the question, "Well, how can we make all schools use ultralearning techniques?" But that's not really my goal. My goal isn't to change the entire way education is done, but rather to change how education is done for the person who picks up my book. To change how they learn a particular skill. If that happens, then I'm more than happy.

Ultralearning is designed for time-constrained self-directed learners who want to tackle a subject that traditionally takes years to master. Unlike a formal education (where you are often motivated by your teacher and/or the classmates around you), ultralearning is often a deeply personal process that requires an extreme amount of self-motivation.

Part of Scott’s motive in writing the book was to reverse engineer these successful ultralearning techniques, making them more accessible. He wanted to show how some of the best ultralearners in the world were able to:

Go from having near-zero public speaking experience to placing as a finalist for the World Champion of Public Speaking in seven months (Tristan de Montebello)

Become the French Scrabble World Champion without speaking French (Nigel Richards)

Go from near-nothing to a million dollars nearly overnight after patiently acquiring all the skills to develop his own game (Eric Barone)

Ultralearning in Action.

Can we apply ultralearning techniques to existing formal education protocols?

The simple answer: Maybe

Let’s start with directness, something that comes up time and time again in Scott’s stories about successful ultralearners.

Directness means learning a skill in the same manner in which you'll apply it, also known as "learning by doing." Directness exposes you to subtle details that you can’t get from theory. For example, you may understand that you need to find the biting point to move a car into first gear, but you can’t learn how the biting point feels by reading about it, you’ve got to get behind the wheel and drive! The transfer method, however, is the method we most commonly used at school for learning a new skill. This method allows you to apply knowledge or skills you have to other situations. Transfer is why a plumber who has never been to your house can fix your sink, they have seen similar problems before. Not exactly the same, yet they can transfer their existing skills and fix the new problem.

Directness works for ultralearning, but it can fail in the context of higher education as it is both hard to teach and measure. This is why transfer is still the primary method used to teach and grade HigherEd courses. Although directness is Scott’s choice for ultralearning, he still sees the transfer method as serving an important signaling role in higher education, as it provides confirmation a student can work abstractly.

SY: There is also a case to be made that a lot of the skills that we need are general transfer. There's no way you can just learn how to do the one and only thing. Often why you're learning physics is not to be able to solve a specific physics problem but to be able to look at the world and be, like, “that's not going to work for this reason.” And that's really hard to teach. It also seems to me that the more prestigious [the university] you get, the less practical you get in terms of the skills being taught, the more they rely on transfer.

So if HigherEd is ultimately focused on the transfer of knowledge, leaving some students short of the practical skills, how will these new entrants into the workforce continue to learn?

EdTech enters the chat...

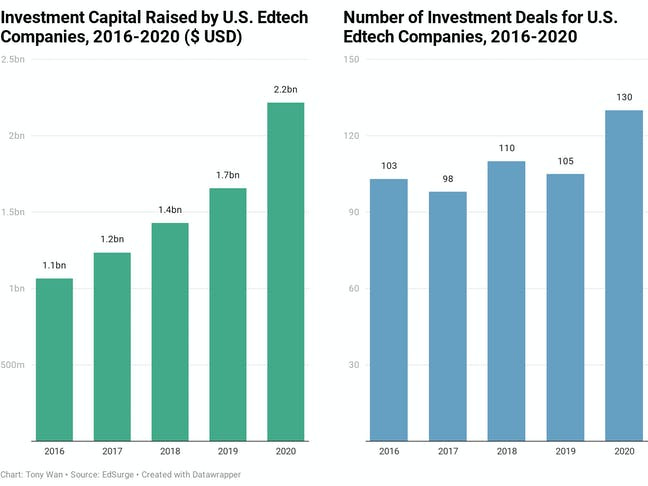

The billion-dollar question for EdTech: can learning methods be designed to suit the individual, not just the crowd, while still growing at the speed and scale representative of the $$$ being raised???

I’ll save this debate for a future newsletter. Now back to Ultralearning.

Are You Willing to Be Bad At Something.

Why isn’t everyone an ultralearner? Scott remarks that we may not all be "ultralearners" but everyone is always learning. Case and point: we all know far more about virology and vaccines in January 2021 than we did this time last year. He adds what often holds us back from learning something new is the anxiety that we’ll have to be bad at it before we see rewards. Not because of our inability.

SY: There's a lot of useful learning that we don't do because it requires this kind of step down. It's difficult to do because we often have a short term focus in our lives. We don't want to make any immediate sacrifices for long term gain. It's also difficult because we attach a lot of status to where we are and what we're doing. So to go back down to a learner perspective, it does sometimes have that feeling of, "Well, I was good at this, and now I'm not good at that. Maybe I should just stick in my lane, stick with what I know." The learning attitude is difficult in that way because it requires the willingness to be bad at something.

Our willingness to be bad at something is central to our ongoing relevance in the future of work. It is central to what needs to shift in order to normalize perpetual upskilling. For Scott, a major goal in writing his book was to encourage people to learn new things. Not by telling people "what they should be doing,” but by inspiring the process of learning. He believes many people have a latent passion to learn. A passion that's often crusted over because of their busy lives, because life's hard, and because it feels like the learning process is going to take forever. We both agree that if we’re to find success in the modern world of work this fear needs to be replaced with motivation, and short term actions need to be replaced with investments in exponential based growth.

Skills as a Form of Power.

So what’s the answer? This is, after all, a lesson, right? Towards the end of our conversation, Scott and I touch on two of my favorite topics promoting lifelong learning.

Unlocking Access to Learning Sabbaticals:

Learning Sabbaticals are both the holy grail for those of us who just want to get paid to learn, and one of the best ways to stay ahead of ever evolving (in-demand) workforce skills. The reality is that the more skills you have, the more negotiating power you will have towards investing time in learning new skills. Scott gives the example of someone being the sole person at their company skilled in hardware design asking for time off to learn a new language. Their employer will more likely say yes to their request, since they're not easily replaced. If the opposite is true, and your skillset is easily replaceable, you’ll probably never be given the time off to get paid to learn.

I’m calling this the skills-fulfilling prophecy.

Storytelling-as-a-Skill

I asked Scott what he thought were the top skills for the modern workforce. The answer, is his own words:

Excel: If you become one of the top 5% users of Excel, it will probably augment whatever other skill you have. Everyone puts Excel on their resume, but I'm talking about being really good at it. Knowing how to do things that other people don't. It's a thinking tool. In contrast, machine learning is overrated. Not because machine learning is unimportant for society or because there aren't incredibly well-paid positions for people doing machine learning, but just that very few organizations need machine learning. Almost all of them use Excel.

Public Speaking: Going from being average to a top 5% public speaker can be a huge career boost. It allows you to speak at conferences, build your network, be the face for projects in your organization. Public Speaking has a huge political benefit beyond just the mere utility of this skill.

Writing: My favorite skill, writing. Most people are terrible at writing. It's also the skill of thinking. To write well you must have clear thoughts. This can be really advantageous, even just from a clarity point of view. If you can write an email that’s really clear to the recipient (what they should take away from it and what actions they should take), you are going to be more effective in an organization. There's going to be a force multiplier for all the work that you do.

The common thread is communication. It is not good enough to have a good idea, but can you share it with the world? Become the top 5% of storytellers in the medium that suits you best (Books, Excel, TikTok, Twitter, etc), and you're bound for success.

Bringing our conversation full circle, it is clear Scott is passionate and excited about everything he learns. He’s prescribed to the notion that self-motivation is key for all adult learning, especially ultralearning. And even though Scott has “cracked the code” when it comes to learning certain types of skills (eg. languages), he still loves the excitement when he is surprised by the outcome of an ultralearning project. It is every learner's responsibility to find those topics they “think are cool,” those topics they are most excited by. And although Scott would love everyone to take advantage of the ultralearning method, what’s most important is to find and focus on the learning outcomes that will provide exponential-based growth for your life!

After School Activities with Scott H. Young:

Read Scott’s book Ultralearning, and check out his most recent articles.

Check out Scott’s different courses and products.

Watch Scott’s keynote on Ultralearning from the 2019 World Domination Summit.